Key findings

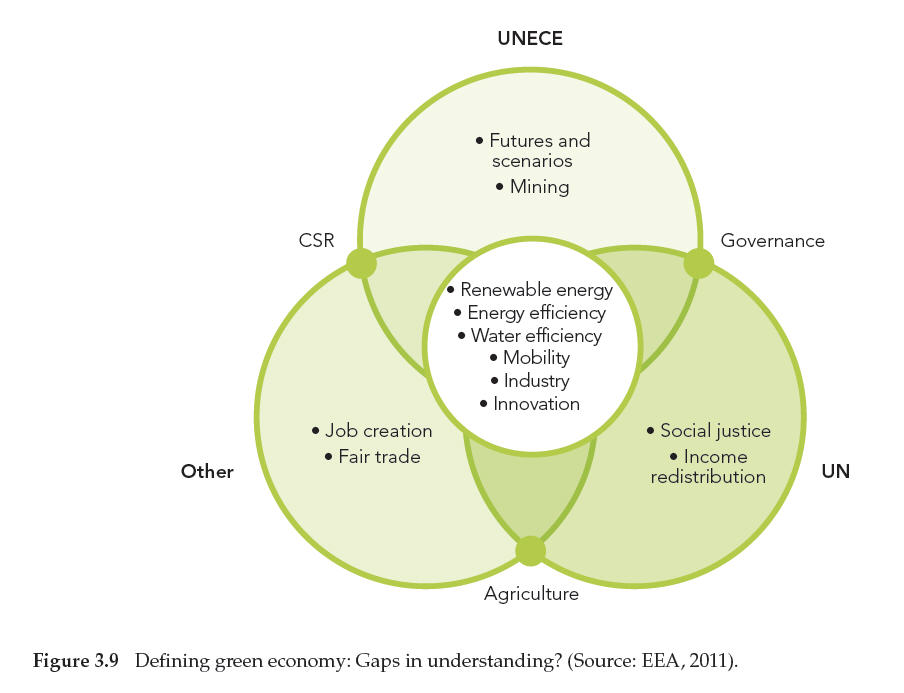

The second theme of the Astana Ministerial Conference is ‘ Greening the economy: mainstreaming the environment into economic development’ . The term ‘ green economy’ is not consistently defined as it is still an emerging concept. The most widely used and authoritative green economy definition comes from UNEP.

[A] green economy [is] one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities (22).

The concept of green economy, in the context of poverty eradication and sustainable development, will attract further attention as it will be one of two key themes at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development to be held in Rio in 2012 (Rio, 2012).

Green economy can refer to sectors (e.g. energy), topics (e.g. pollution), principles (e.g. polluter pays) or policies (e.g. economic instruments). It can also describe an underpinning strategy, such as the mainstreaming of environmental policies or a supportive economic structure.

Resource efficiency is a closely related concept, since the transition to a green economy depends on meeting the twin challenges of maintaining the structure and functions of ecosystems (ecosystem resilience) and finding ways to cut resource use in production and consumption activities and their environmental impacts (resource efficiency).

Whatever the underlying approach of green economy is, it stresses the importance of integrating economic and environmental policies in a way that highlights the opportunities for new sources of economic growth while avoiding unsustainable pressure on the quality and quantity of the natural assets. This involves a mixture of measures ranging from economic instruments such as taxes, subsidies and trading schemes, through regulatory policies, including the setting of standards, to non-economic measures such as voluntary approaches and information provision.

Although no comprehensive assessments covering the priority themes of green economy and resource efficiency as applied in the EE-AoA exist, broad strategies for greening the economy (a dynamic rather than static process) or specific theme-based assessments have been undertaken at national, regional and global levels by a range of public and private sector organisations.

Most assessments cover well-established themes, such as energy, industry and governance (green economy), and use of natural capital (resource efficiency). However, far fewer cover other important (often newer) aspects of green economy, including futures and scenarios, environmental impact assessment/strategic impact assessment (EIA/SIA), corporate social responsibility (CSR), life-cycle analysis (LCA), and finance, trade and tourism.

Assessments are overwhelmingly focused on the state of different priorities, and this is particularly the case for the more well-established or traditional themes. Other aspects of the DPSIR framework (drivers, pressures, state, impacts and responses) are discussed much less frequently.

Countries worst affected by the global recession emphasise green jobs and growth in their recent assessments. Assessments covering the energy sector are widespread and focus on renewable energies and energy efficiency. In addition countries dependent on primary and extractive sectors also tend to emphasise natural resource efficiency.

Effective assessments require a green economy strategy to be at the very heart of the national or regional decision-making process. Currently, assessments address policy questions in specific but generally narrow areas, for example, related to an increased proportion of renewable energy, to green public procurement or to green jobs. It is less clear how assessments, even those of the more strategic variety, are being used to drive economic policy in general. If the green economy is about transforming the way a nation produces and consumes, trades and is governed, then assessments should be at the very heart of economic and political strategies, rather than at the fringes.

Main findings of green economy related assessments

Although there are no fully integrated green economy assessments in the pan-European region, the following findings can be drawn from the mainly theme-based assessments:

- A framework to promote a green economy is lacking. Currently, assessments are largely driven from the bottom-up and do not generally form part of a clear ‘ top-down’ framework.

- Green economy is not defined clearly and consistently. It is still a novel concept and refers to a mix of existing and emerging sectors, topics, principles and concepts. Most assessments focus on one or more of these topics, but very few take a more integrated approach, encompassing a range of concepts or the whole of the DPSIR framework.

- There is often no clear link between an assessment and the decision-making process, and many assessments do not articulate objectives or key questions to address, following rather than informing policymaking.

- Institutional arrangements are unclear, with a wide range of organisations and ministries involved but limited coordination either between or within regions and countries, or between the public and private sectors. This leads to some overlap in assessments and reduces effectiveness in policymaking.

- The objectives of the assessments are not always clearly defined. This contributes to a lack of focus in many assessments. There are also relatively few ex-post assessments that evaluate policy or consider how assessments have led to adoption of policies.

- Assessments are numerous, but often large and unfocused, producing a mosaic of fragmented, overlapping and divergent assessments. In addition, the assessment universe is constantly expanding, but in an uncontrolled way and there is currently a lack of consistency in and comparability of the basis, format and frequency of data being collected and used.

- There are clear regional differences in assessments, with some themes (e.g. sustainable consumption and production (SCP), innovation) concentrated in EEA member countries and others (e.g. governance, energy) most prevalent in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia and the Russian Federation.

A large number of assessments also identified concerns and emerging needs including:

- Countries and organisations tend to be selective in the themes considered. This flexibility may ‘ water down’ the green economy concept to the point that it becomes almost meaningless.

- Institutional complexity associated with undertaking assessments leads to poor coordination, overlapping competencies and lack of effective change.

- Progress towards a green economy is hampered by insufficient financing, a limited use of economic instruments or political emphasis on other issues.

- There are information gaps at both spatial and temporal levels, partly due to the lack of monitoring systems, inconsistent data and inadequate data flow mechanisms.

3. Green economy

The second key theme of the Astana Ministerial Conference is Greening the economy: mainstreaming the environment into economic development. The objective of this chapter is to review the current state of assessments relating to the green economy and to resource efficiency. This will help lay the foundations for focused pan-European reporting and assessment processes, and aid decision-making in the region within these broad overarching concepts central to environmental improvement.

There is first a review of how these concepts are defined and the various institutions — national, regional and international, public and private — involved in assessments (Section 3.1). Then a consideration of the detail of currently available assessments (Section 3.2), how they are developed and how they are used. In Section 3.3 there is a discussion of how assessments might evolve in the future to address current concerns, emerging issues and key gaps and, finally, some conclusions are given and recommendations made (Section 3.4).

3.1 Introduction and background

3.1.1 Setting the scene

There are 675 reports in the EE-AoA portal relating to elements of the green economy or resource efficiency but, as yet, there are no integrated assessments that bring together all relevant elements in a coherent fashion in the pan-European region. This is largely because there is no widely accepted definition of the green economy and its scope.

The term ‘ green economy’ was first coined in Blueprint for a Green Economy (Pearce et al., 1989), a key text for proponents of this still emerging discipline which is principally concerned with the economics of sustainable development.

Since the launch in 2008 of the United Nations’ Green Economy Initiative (GEI), one of nine joint crisis initiatives (23), there has been a proliferation of interpretations and definitions. A number of other terms, including ‘ green growth’ and ‘ greening the economy’ , have also been widely adopted and used interchangeably in connection with an ever increasing number of economic sectors, such as energy and water; topics for example, mobility and consumption; and concepts such as the polluter pays principle and life cycle analysis.

The most widely used and authoritative definition comes from UNEP (2011a):

[A] green economy [is] one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities.

The important links between green economy and sustainable development are also well-recognised:

The concept of a ‘ green economy’ does not replace sustainable development, but there is a growing recognition that achieving sustainability rests almost entirely on getting the economy right.

Decades of creating new wealth through a ‘ brown economy’ model based on fossil fuels have not substantially addressed social marginalisation, environmental degradation and resource depletion. In addition, the world is still far from delivering on the Millennium Development Goals by 2015 (UNEP, 2011a).

Indeed, the green economy, in the context of poverty eradication and sustainable development, will be one of two key themes at the Rio 2012 Summit (24).

The concept of green growth stresses the importance of integrating economic and environmental policies in a way that highlights the opportunities for new sources of economic growth while avoiding unsustainable pressure on the quality and quantity of natural assets (OECD, 2011a and 2011b). The transition towards a green economy involves a mixture of measures ranging from economic instruments such as taxes, subsidies and trading schemes, through regulatory policies including the setting of standards to non-economic measures such as voluntary approaches and information provision.

The green economy can also be viewed as a set of principles, aims and actions, which generally include (ECLAC, 2010; EEA, 2010; UNEP 2011a; and OECD, 2011a):

- equity and fairness, both within and between generations;

- consistency with the principles of sustainable development;

- a precautionary approach to social and environmental impacts;

- an appreciation of natural and social capital, through, for example, the internalisation of external costs, green accounting, whole-life costing and improved governance;

- sustainable and efficient resource use, consumption and production;

- a need to fit with existing macroeconomic goals, through the creation of green jobs, poverty eradication, increased competitiveness and growth in key sectors.

Resource efficiency is implicit in the green economy’ s principle of sustainable and efficient resource use, consumption and production. In this context, the EEA State and outlook 2010 (EEA, 2010) argues that the transition to a green economy depends on meeting the twin challenges of maintaining the structure and functions of ecosystems (ecosystem resilience) and finding ways to cut resource use in production and consumption activities and their environmental impacts (resource efficiency).

More specifically, resource efficiency means achieving a desired increased level of output with a reduced level of human, natural or financial inputs. It is a necessary criterion for a green economy, although it may not be sufficient, as it may still allow resource use to increase in absolute terms, which indeed has been the case for most countries in recent decades (OECD, 2011c).

Compared to green economy, measures of resource efficiency are easier to define (UNEP, 2010a). At the macroeconomic level, indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP) per resource use highlight the relationship between resource use and economic output. Nevertheless, differences in interpretation remain, with only a few countries formally defining the term ‘ resources’ in policy. Some include both renewable and non-renewable resources, while others use a narrower term ‘ raw materials’ which includes fossil fuel reserves. Neither a clear definition nor a common understanding of the term ‘ resource efficiency’ appears to be in place (EEA, 2011).

Any green economy model needs to define what the concept means and includes. Box 3.1 lists the priority areas for green economy and resource efficiency as developed by the UNECE Committee for Environmental Policy (CEP) and Annex 3.1 sets out a brief explanation of these priorities, how they are related to the green economy and some examples showing how it is being advanced in Europe.

Some key observations emerge from Annex 3.1:

- some priorities are easier to define than others. For example, renewable energy and tourism are sector specific, even though their impact is felt elsewhere. Others such as mobility and sustainable consumption and production (SCP) are more topic-based and not associated with any specific sector;

- some priorities, energy efficiency for example, are characterised in some regions at least by clear policy frameworks and targets and some, including Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), are the subject of international conventions and/or legal instruments. Others — life cycle analysis (LCA) for example — are less clearly identified and are therefore more difficult to measure or target and are typically associated with broad strategies or action plans;

- policy drivers can be roughly grouped as either environment-related such as pollution reduction, or economics-related resource costs, economic reform, trade, for example. Such EU policy initiatives as the Europe 2020 Strategy are a strong driver in many countries, including candidate countries;

- green economy priorities have a wide range of drivers, including climate change, economic recovery, protection of biodiversity and demographic change.

Box 3.1

Theme priorities regarding green economy and resource efficiency

Green economy

- Renewable energy (including hydropower, biofuels and biomass);

- Energy efficiency;

- Mobility (air quality, emissions and noise);

- Industry (emissions and waste);

- Innovation;

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Impact Assessment (SIA);

- Governance (including institutional arrangements and multilateral environmental agreements) and environmental performance reviews;

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and environmental reporting;

- Mining.

Resource efficiency

- Use of natural capital (including forestry, agriculture, urbanisation linked to the use and degradation of land, soil, water and biodiversity);

- Water efficiency in industrial, rural and urban areas;

- Life-cycle analysis;

- Environmental accounting;

- Sustainable consumption and production patterns;

- Tourism.

Note: The two priority areas ‘innovation’ and ‘mining’ were added by the EEA in view of their relevance for the topic and geographical coverage addressed by the report (Source: Steering Group on Environmental Assessments (http://www.unece.org/env/efe/Astana/SGEA/1stMtg/ OutlineAoA_e.pdf).

Given the current lack of integrated green economy assessments, the analysis of the green economy related reports included in the EE-AoA portal is organised according to the priority areas agreed by the UNECE Steering Group on Environmental Assessments. This approach enables the consideration of all assessments that address at least one of the priority areas.

3.1.2 National green economy related assessments

No country in the pan-European region has yet produced an assessment specifically focused on the green economy. Nonetheless, many countries are developing broad strategies for greening the economy, or have undertaken sectoral or topic-based assessments.

The breadth of interpretation of the green economy concept at a national level, and the fact that it encompasses a range of sectors and priorities, is reflected in the diversity of institutions involved in its promotion. Some of these are responsible for different aspects of the priority areas, while others coordinate production of the selected assessments.

Environment ministries typically take the lead, have an overview of green economy and resource efficiency, and are charged with bringing different priorities within these concepts together. However, the scope and areas of responsibility of these ministries alone vary enormously and reflect broader national priorities and political boundaries. For example, an environment ministry may be largely responsible for nature protection (Armenia) or may also be responsible for tourism (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and natural resources, including mining and oil (Belarus) or agriculture (Austria, Hungary and the United Kingdom).

Depending on the institutional arrangements of the country, other ministries may also be involved in the contribution of particular elements of broader green economic goals. Indeed, 65 per cent of assessments related to the green economy involve more than one national organisation.

Other ministries involved include transport, agriculture and forestry particularly in more rural-based economies. Furthermore, the ministries of finance and economy are playing a decisive role in the green economy discussion, for example in the Republic of Moldova the Ministry of Economy oversees the country’ s Energy Strategy; as well as a Ministry of Energy in countries with natural energy reserves or which are developing renewable energy. In the Russian Federation, the Ministry of Natural Resources has come together with the Federal State Statistics Service, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry for Economic Development and others to develop natural resource accounting and promote inter-agency coordination and cooperation.

A number of other departments and ministries are also starting to play a greater role in a few countries, reflecting the increase in cross-sectoral strategies and action plans. These include housing, culture, business and trade, skills and innovation and education.

In most countries, the national environment agency also plays a significant role in monitoring progress using environmental indicators related to the green economy and in producing or contributing to national assessments.

In several countries, assessments are also undertaken at a devolved administrative level. For example, assessments related to air quality in Belgium include an Air and Climate Plan for Brussels, a Flemish Climate Policy Plan, and a separate State of the Environment Report, with an assessment of air quality, for Wallonia.

Assessments by national organisations not part of the pan-European geographical area

The UNECE member countries which are not part of the pan-European geographical area also undertake green economy assessments, and can offer some valuable insights and lessons.

In the United States of America, assessments focus on the contribution of green growth to wider economic recovery, as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (US Department of Commerce, 2010). This committed the federal government to invest USD 90 billion to promote innovation and growth in green business and jobs. Similar definitions, such as pollution control, resource conservation and environmental assessment, are used but a distinction is drawn between narrow and broad definitions — the latter including nuclear energy and other products and services which are in general not considered green.

In Canada too, growth and jobs are central to the debate around the green economy (e.g. UNEP, 2008 and 2011a). However, given the importance of primary industries to much of the economy, natural resource protection also plays a prominent role in the green economy debate (e.g. Globe Foundation, 2010).

Discussion of the concept of a green economy can also be found beyond the UNECE region and member countries (e.g. UNEP, 2010b). In Latin America and the Caribbean, green economy is framed largely in terms of helping to address poverty and inequality, and in delivering basic infrastructure and services for a growing population (ECLAC, 2010). These regions are at the forefront of putting green economy concepts into action in some sectors. For example, Costa Rica, which is heavily dependent on its natural ecosystems for tourism, has been a pioneer in the use of economic instruments and payments for environmental services to promote activities that preserve ecosystem functions (Russo and Candela, 2006; and OAS, 2010).

3.1.3 Assessments by public organisations

Although the number of dedicated green economy assessments produced by national organisations is limited, other publicly funded, pan-European and international organisations are interested in the green economy and involved in producing assessments related to the priority areas.

Broadly, three types of organisation can be distinguished: global players, including UN organisations such as the FAO, UNEP and UNDP; regional UN bodies, including UNECE; and other regional organisations.

i) Global players

Most currently available international assessments are global in nature, with international organisations playing a key role in developing thinking on the green economy and resource efficiency issues. UNEP has produced a number of these, notably the Global Environmental Outlook (GEO) series. This is a process that builds capacity for conducting global environmental assessments and for reporting on the state and trends of the environment, future outlooks and policy options. GEO-5 will be published in 2012, as a key input to the Rio 2012 Summit.

UNEP’ s Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication (2011a) is the most recent and definitive work to date on global green economy. It argues that a two per cent injection of global GDP into ten key economic sectors would kick-start a transition towards a low carbon, resource efficient green economy. The underlying concept of starting the process through a fiscal stimulus package is drawn from the UN call for a Global Green New Deal (25). The assessment also includes global indicators of progress on relevant priorities showing how these link to GDP using case studies from around the world.

UNEP also works in collaboration with other bodies on specific issues. For example, a joint report with the International Labour Organisation (ILO) assembles quantitative and conceptual evidence on existing green jobs (UNEP, 2008). Another example is the forthcoming report on organic agriculture revealing that organic agriculture can re-vitalise the farm sector and create employment opportunities (UNEP, 2011b).

Another UN body, UNDP, plays an important role in green economy related assessments in several countries, notably in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Western Balkans. Here, assessments are driven by the desire to build capacity and to enhance competiveness from the more efficient use of natural capital through technical or financial assistance programmes.

A recent assessment in the Russian Federation provides a detailed analysis of the situation in the energy sector, makes forecasts and examines options for overcoming current negative trends in supply and consumption of energy resources (UNDP, 2009). Another report looks at the opportunities for Georgia in a new green economy (UNDP, 2010).

Other relevant global organisations include FAO, the World Bank and the IMF. The FAO is exploring the global resource and health footprints of agriculture and food systems as part of its ongoing Greening the Economy with Agriculture (GEA) initiative. The World Bank is developing national indicators that can be used by finance ministries in green national accounting. The World Bank’ s latest publication in this area The Changing Wealth of Nations (World Bank, 2011) shows a clear link between the careful management of natural capital and increasing levels of wealth and economic wellbeing. Box 3.2 shows some of the work being done by global organisations.

Whilst global organisations focus on global assessments, they also consider regional priorities and topics. Two examples are UNEP’ s assessment of aquatic ecosystems in the Baltic Sea (UNEP, 2005) and UNEP’ s assessment of mining and the environment in the Western Balkans (UNEP, 2009a).

ii) Regional UN players

The UNECE area covers a pan-European region including all 53 countries included in the EE-AoA exercise (26). Work on the green economy is driven mainly through the Environment for Europe partnership and regular environmental performance reviews. Furthermore, UNECE Timber Committee and FAO European Forestry Commission are jointly preparing an action plan for the forest sector in the green economy.

The other key regional UN player is UNESCAP (27). This has been at the forefront of the green economy debate in the Asia-Pacific region since the Ministerial Conference on Environment and Development in Asia and Pacific in Seoul in 2005, when the Seoul Initiative on Environmentally Sustainable Economic Growth (Green Growth) was established.

Box 3.2

Global organisations and the green economy

FAO — Greening the Economy with Agriculture (GEA) (28)

Greening the Economy with Agriculture refers to increasing food security (availability, access, stability and utilisation) while using fewer natural resources, through improved efficiencies throughout the food value chain. This can be achieved by applying an ecosystem approach to agriculture, forestry and fisheries management in a way that addresses the multiplicity of societal needs and desires, without jeopardising options for future generations to benefit from all goods and services provided by terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Using 60 per cent of world’s ecosystems and providing livelihoods for 40 per cent of today’s global population, the food and agriculture sector is critical to greening the economy. For FAO, there will be no green economy without agriculture.

World Bank — Changing Wealth of Nations (29)

This is the latest assessment by the World Bank to estimate comprehensive wealth — including produced, natural and human/institutional assets — for more than 100 countries.

The report presents wealth accounts for 1995, 2000, and 2005, providing the first longer-term assessment of global, regional, and country performance in building wealth. This assessment is complemented by chapters detailing individual components of wealth, as well as how countries and the World Bank are using comprehensive measures of wealth for policy analysis.

IMF — Green Growth (30)

The IMF has spoken of the need for a low-carbon model for growth as the world rebuilds from the global economic crisis.

To help finance this shift in the global economy, the IMF is working on proposals to create a multi-billion dollar Green Fund that would provide the huge sums, which could climb to USD 100 billion a year in a few years, needed for countries to confront the challenges posed by climate change.

A key aspect of UNESCAP’ s work on green economy is the Astana Green Bridge Initiative (UNESCAP, 2010; and UNECE, 2011). This promotes green economy principles in relation to changing political and economic conditions, environmental priorities and the growing needs of the countries of Europe, Asia and the Pacific. A proposed partnership programme to implement the initiative will introduce specific targets, funding and evaluation (UNECE, 2011).

UNESCAP recently funded the only existing national green growth assessment in Central Asia (Box 3.3).

UNESCAP is also active in the resource-efficiency debate (UNESCAP, 2011). A forthcoming report will consider the regional use of key resources, and what that means for economies in the Asia-Pacific Region (UNEP, 2011c).

Box 3.3

National report on integration of green growth tools in the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2010

This assessment, prepared by the Network of Experts for Sustainable Development of Central Asia (NESDCA), reviews approaches to and principles of the green growth concept, analyses the use of its instruments in Kazakhstan by, for example, assessing eco-efficiency, and provides conclusions and recommendations on their integration into strategic planning processes.

Recommendations of the assessment include:

- the introduction of green growth principles into the system of strategic planning and taxation;

- the introduction of economic green growth tools;

- the development of green business and infrastructure;

- the introduction of sustainable production and consumption.

Source: http://www.nesdca.narod.ru/publications_eng.html.

iii) Other regional players

Other institutions with a regional (i.e. covering more than one country) interest in or perspective on the green economy range from the relatively small, such as the Baltic Agenda 21, to the very large, the OECD and European Union.

These players vary in terms of their governance, geographical interest, scope for undertaking assessments and decision-making powers. In general, smaller organisations are involved in topic specific assessments, on, for example, air pollution or solar power generation, while larger organisations tend to look across such topics as SCP, or produce broad pan-regional topic- or sector-based assessments.

The drivers for assessments from these bodies also vary markedly. Some stem from the desire to transfer resources, technologies and environmental protection programmes to new areas (OECD, 2010, 2011a and 2011b), others by the need for environmental compliance or in response to specific threats from pollution. For example, Helcom (31) produces integrated assessments on eutrophication and other issues of concern in the Baltic Sea area.

In Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, the Regional Environment Centres (RECs) have taken a leading role in producing and coordinating strategies, action plans and regional assessments.

The OECD published an Environmental Outlook to 2030 (OECD, 2008). This represented a shift in attitude and outlook from a traditionally free-market based and growth-driven organisation. It recognises the importance of natural capital, resource efficiency and other green economy related concepts in delivering sustainable growth. Indeed, the organisation is increasingly at the forefront of attempts to embed the concepts of natural capital, resource efficiency and greener growth into economic development across much of the pan-European region (OECD, 2011c and 2011d). Furthermore, the OECD launched its green growth strategy at the OECD Ministerial Council Meeting in May 2011 (OECD, 2011a and b).

The EU and other European institutions (32) are involved in various aspects of the green economy and produce regional and country assessments. The EU produces an annual monitoring report on the implementation of its sustainable development strategy, which covers most of the priority areas related to the green economy and resource efficiency (Eurostat, 2009). It also uses the EU Cohesion Policy to invest in priority areas which are part of the green economy in the Balkans and other regions.

Most recently, the European Commission is preparing a Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe, part of the wider Europe 2020 Strategy (33). This encompasses a number of initiatives, including energy efficiency, carbon and commodity markets. It identifies increasing resource efficiency as key to securing improvements in productivity, competitiveness, growth and jobs.

EEA regularly produces ‘ State and outlook’ reports (SOER) covering its member countries and more recently cooperating countries. The most recent SOER (EEA, 2010) includes consideration of aspects of the green economy. The EEA has also supported the EfE process since the beginning and produced upon the ministers’ request pan-European State of environment report which also examined aspects of the broader green economy such as energy, SCP, water, waste, etc. The most recent report was published for the 2007 EfE Belgrade Conference.

USAID undertakes assessments in many pan-European countries and has recently assessed biodiversity in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine, identifying threats, actions necessary to address them, and the extent to which USAID actions meet these needs (34).

3.1.4 Assessments by the private/voluntary sector

A large number of private or voluntary, non-governmental organisations are involved in assessing aspects of the green economy. These broadly fall into four categories:

- non-governmental organisations, charitable foundations and lobby groups. These generally have a specific remit or cause. For example the Living Planet Report produced by the World Wide Fund for Nature measures the health of the world’ s biodiversity in relation to humanity’ s demands on the Earth’ s natural resources (WWF, 2010);

- think-tanks and multinational organisations — for example the World Resources Institute. These are primarily concerned with improving the knowledge base and ensuring latest thinking is brought into decision-making, e.g. the climate analysis indicators tool (35) ;

- national, regional and international trade associations. These are generally interested in promoting specific viewpoints and influencing decision-making. An example is the role of steel in reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions (World Steel Association, 2010);

- research bodies, including universities and research institutes which may attract funding from private sector sources (e.g. The Agency for Rational Energy Use and Ecology in Ukraine and the Stockholm Environmental Institute, 2009).

Again, there is very little consistency across regional non-governmental organisations in terms of the size or type of region they cover, and in their interests, which include trans-boundary ecosystem issues, the Baltic Sea 2020 for example, through to a broad range of trans-regional economic issues in the case of the Asian Development Bank.

Increasingly, organisations from the private or voluntary sectors are working in partnership with publicly funded organisations to produce assessments. For example, the global insurance industry worked with UNEP to improve understanding of the role of that industry in a greener economic future. The report (UNEP, 2009b) concluded that

… through the systematic integration of material environmental, social and governance factors into core insurance processes, insurance companies will be able to sustain their economic activities and play their roles in the creation of a more sustainable global economy that invests in real and inclusive long-term growth, genuine prosperity and job creation, in line with UNEP’ s Green Economy Initiative.

The European Investment Bank is at the forefront of other public-private partnerships (PPP). It has invested significantly in renewable energy, energy efficiency, transport, the protection of biodiversity and many other areas in EU Member States, candidate countries and other parts of the pan-European region. Assessments focus on the effectiveness of specific PPP projects that protect and improve the natural and built environments and foster social well-being, in support of EU policy (Ecologic, 2011).

3.1.5 Overview of key green economy and resource efficiency assessments

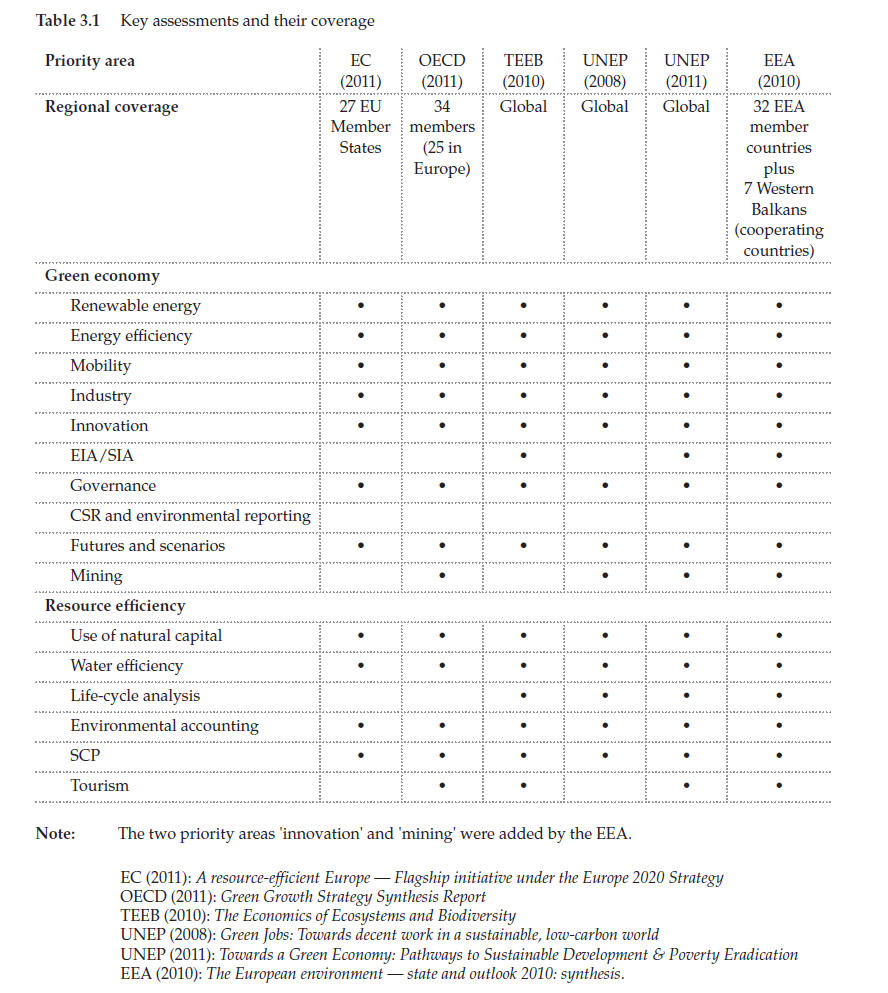

In summary, very few assessments specifically focused on green economy have been undertaken to date. Those that have tend to have been produced by large global or regional organisations. Table 3.1 provides an overview of the coverage of the key assessments from a selection of these organisations in relation to the priority areas of green economy and resource efficiency.

At this level, assessments are reasonably consistent in their interpretation of green economy, although there are some differences at the edges. This interpretation is rather broad and typically characterises a green economy as one which is low carbon, resource efficient and socially inclusive, and sees it as mainly driven by private and public investment.

3.2 Overview of green economy related assessments

In this section, the general findings of Section 3.1 are built on to provide a more detailed analysis of green economy and resource efficiency priorities in assessments. This section is mainly based on information in the EE-AoA virtual library, review templates and country fiches, and on Annex 3.2, which provides an overview of assessments in each priority area, covering:

- number and frequency of assessments (is the area well served by assessments and how often are they produced?);

- size and type of assessments (for example, are they strategic or developed in response to specific policy priorities);

- main developments (for example, do they follow DPSIR assessment framework? (36) Do they identify new or emerging threats and opportunities?);

- basis of assessments (for example, whether they show progress over time);

- geographical aspects (are some parts of the pan-European region better covered by assessments in the area than others?).

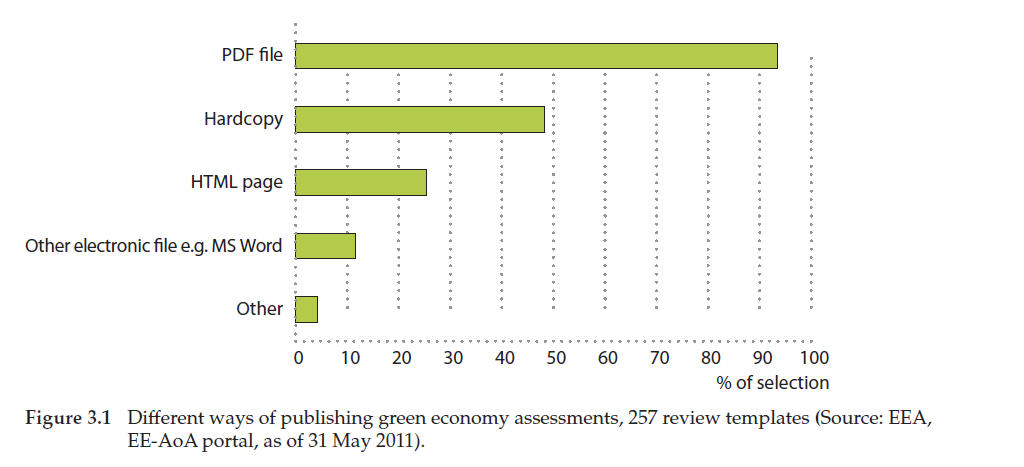

Out of the total number of entries in the EE-AoA portal related to the green economy or resource efficiency, 257 assessments were reviewed in detail using the EE-AoA review template (37). Furthermore, from these 257 reviewed assessments, only 56 per cent are part of a regular process for assessment — generally as part of a ‘ state of the environment’ report — with most of the remainder produced on a more ad-hoc basis. Nearly all assessments are now made available online (93 per cent in pdf format), although hard copies are still made available in 48 per cent of cases. Figure 3.1 shows the different ways assessments in this area are made available.

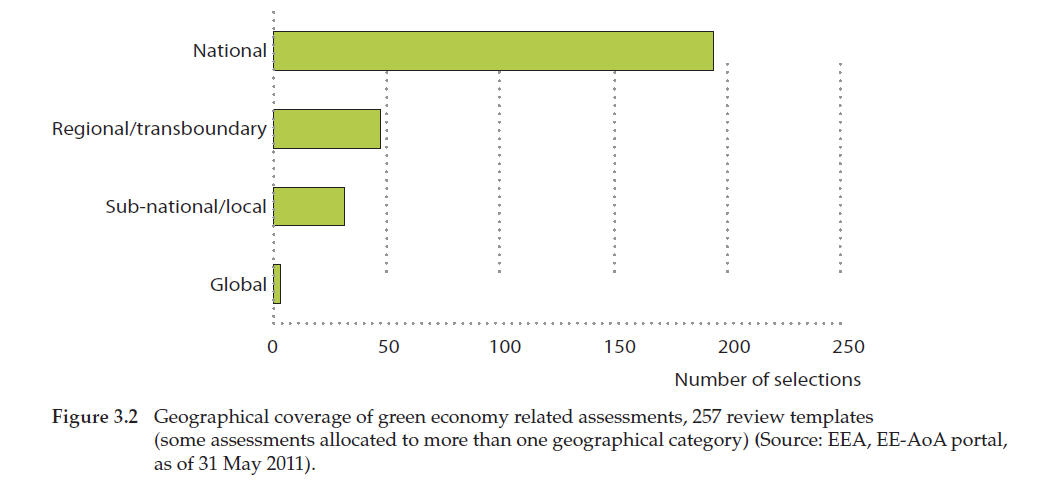

The breakdown of the assessments by geographical coverage is shown in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 shows that the majority of assessments are undertaken at a national level, with a smaller number undertaken at either local or regional level, and only very few at a global level.

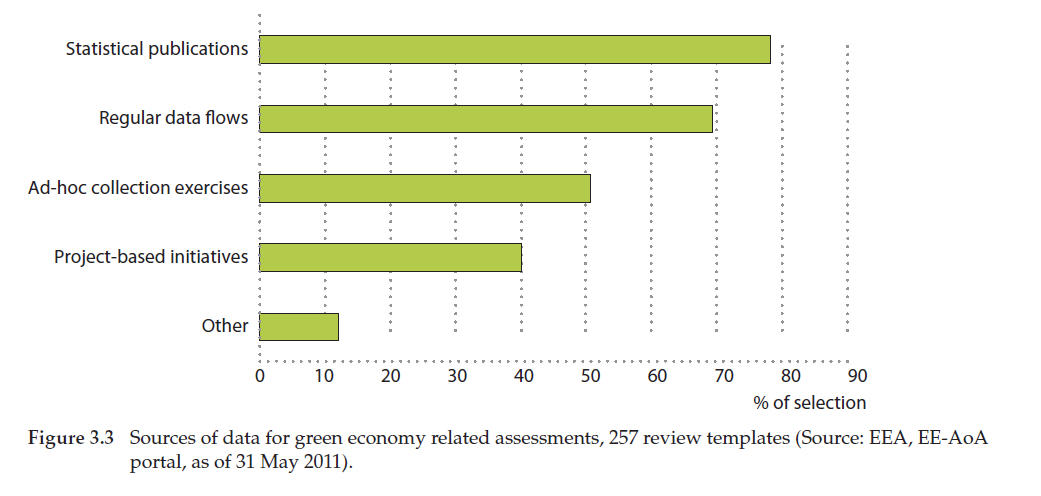

Figure 3.3 summarises the sources of data that are used for green economy assessments. This shows that statistical publications are the most widely used data source, followed by regular data flows, ad-hoc collection exercises and project-based initiatives.

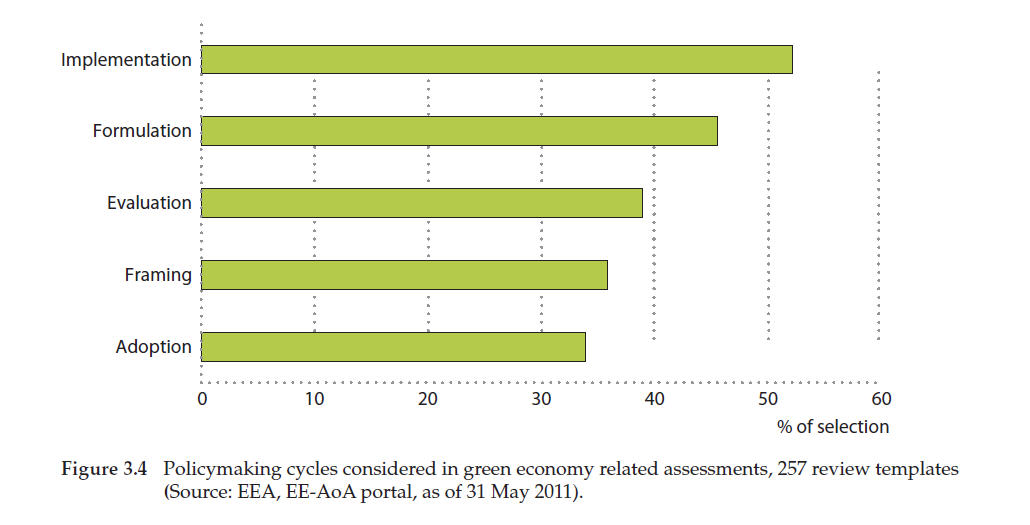

Around three-quarters (72 per cent) of green economy related assessments consider options for the future. Figure 3.4 summarises the kind of policymaking options that are considered in assessments. The figure shows that around half of green economy assessments that consider policy options look at formulation and implementation of policy. Rather fewer look at policy adoption, framing and ex-post evaluation.

3.2.1 Assessments as part of wider reports

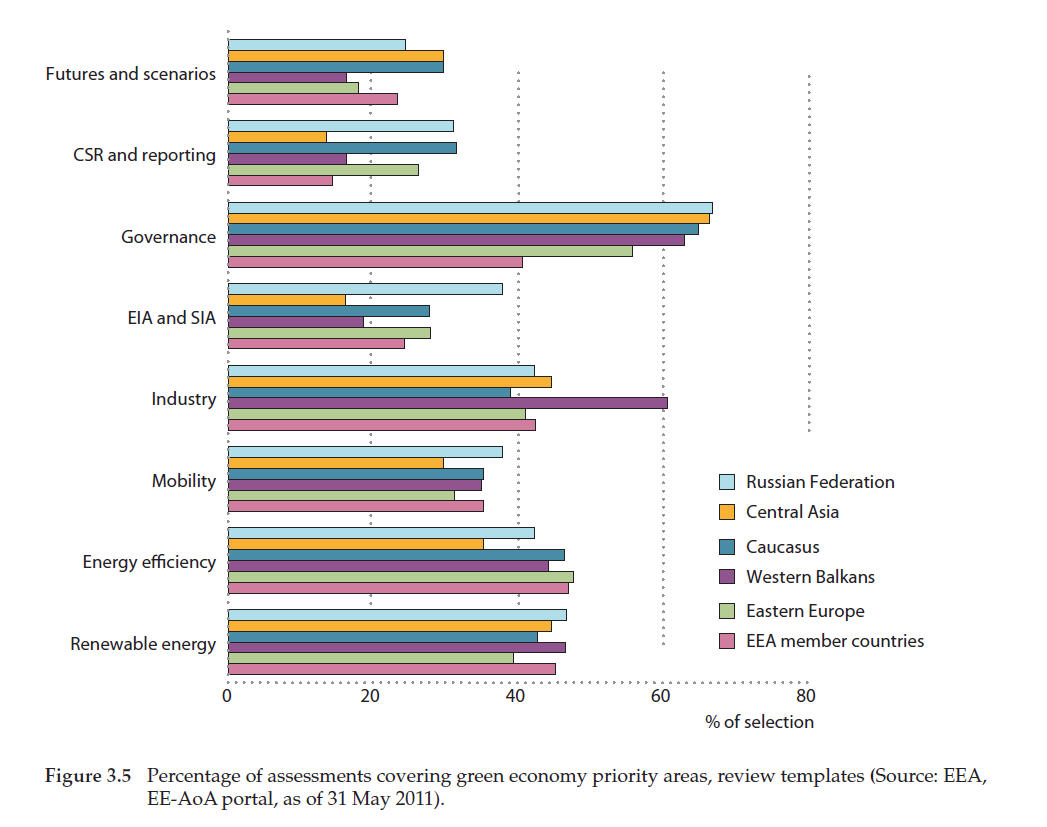

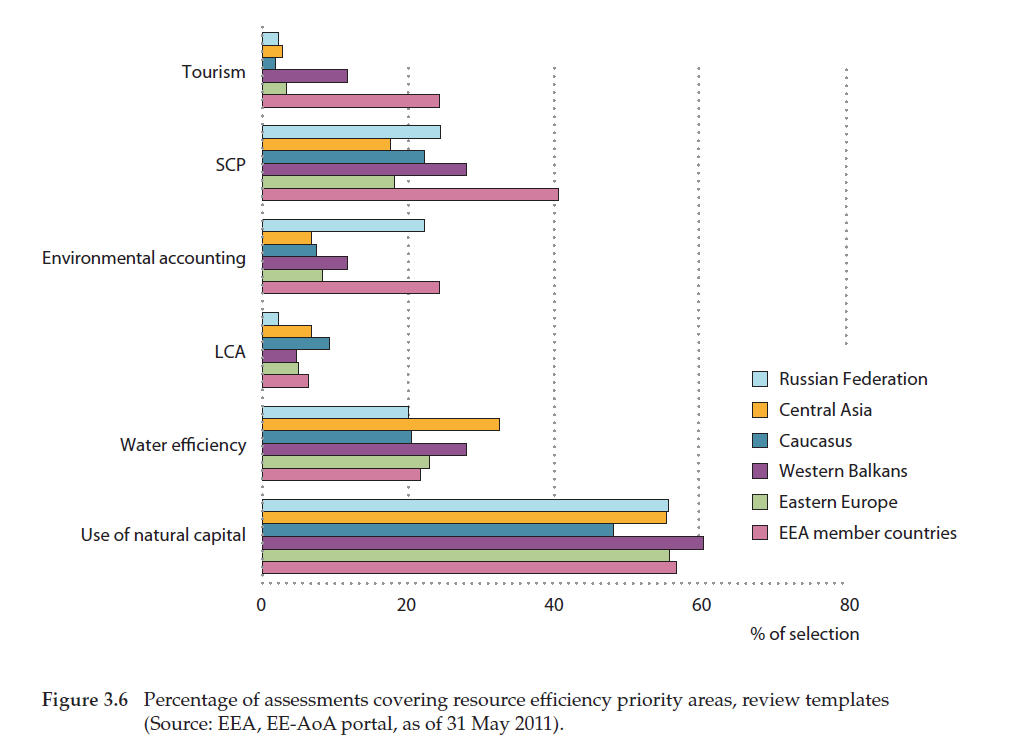

As seen in Section 3.1, there are a variety of ways of defining green economy and resource efficiency. Figures 3.5 and 3.6 summarise the priority areas covered under green economy and resource efficiency assessments across each part of the pan-European region (38).

Figures 3.5 and 3.6 show that, in terms of the topics covered, there is high consistency within the priority areas but low consistency and high variability between the priority areas of green economy and resource efficiency as presented in Box 3.1.

Most assessments discuss the well-established themes of energy, industry and governance (green economy), and use of natural capital (resource efficiency), with regular and detailed assessments as highlighted in Annex 3.2. For example, many countries produce an annual progress report on renewable energy generation. On energy efficiency, Georgia has recently completed a review of the potential for growth and policy options (World Enterprise for Georgia, 2008). However, far fewer discuss other important aspects of green economy, including futures and scenarios, Environmental Impact Assessment/SIA (green economy), LCA and tourism (resource efficiency). Likewise there is much poorer coverage of newer aspects, such as CSR and environmental accounting. As well as national level assessments, a significant number come from global or regional organisations, for example, IISD (2011) or from private bodies such as the Carbon Disclosure Project (39).

Part of the reason for this is that some of these environment-related areas have only relatively recently been added to the more traditional aspects of assessments and may be voluntary or unrelated to specific policy or legislative drivers. Examples include the Russian Federation’ s and Portugal’ s ‘ state of the environment’ reports, which now include information on the areas under organic farming, and Serbia’ s, which discusses gross nutrient balance. Other topic areas gaining more attention include natural capital and green accounting, green skills, and linking the green economy to competitiveness.

Assessments in Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Russian Federation, Eastern Europe and Western Balkans tend to focus on organisational and compliance issues (i.e. governance) as well as on more traditional economic issues such as industry (particularly in the Western Balkans). Less attention is generally given to such aspects as energy efficiency, SCP and environmental accounting. This may be a by-product of the transition to the market economy; with these countries not yet stable and mature enough in economic terms to focus on or commit to obligations beyond the bare minimum.

In general, EEA member countries are more likely to discuss key aspects of resource efficiency in assessments, particularly tourism, SCP and environmental accounting. However, tourism is also important in the Western Balkans.

The space dedicated to the green economy and resource efficiency in recent SoE assessments varies markedly, from around 10 per cent for the United Kingdom to more than 90 per cent for Serbia and Belgium (see EE-AoA portal for more details of these reports). On average, the twin themes account for about 55 per cent of reviewed ‘ state of environment’ reports, compared to 63 per cent of environmental performance reviews and 38 per cent of statistical yearbooks or sets of indicators.

Analysis shows that the amount of attention given to the green economy and resource efficiency issues is related to national priorities and policies. For example, as one leading tourism destination in the Adriatic Sea, Croatia’ s ‘ state of the environment’ report (see EE-AoA portal) includes a discussion of tourism, which is not such a high priority in other countries’ reports. In other countries, certain aspects of the green economy are considered particularly important, mining in Kazakhstan, for example. Many aspects of the green economy or resource efficiency also feature in generic chapters or discussions, for example on water efficiency, which is discussed in relation to households, agriculture and industry.

A number of assessments are very large and detailed, often running to hundreds of pages. This is true of ‘ state of the environment’ reports Belgium — Wallonia, 698 pages, with the green economy or resource efficiency issues accounting for 91 per cent of this; environmental performance reviews — Uzbekistan, 201 pages with 43 per cent dedicated to green economy/resource efficiency issues; and statistical yearbooks — Belarus, 559 pages, 27 per cent of which is on green economy or resource efficiency. Despite the often great detail of some of these assessments, relatively few provide a summary (only 22 percent in the case of ‘ state of the environment’ reports).

Most countries produce statistical assessments annually. Some countries, including Armenia, Belarus, Croatia and Ireland, produce more detailed ‘ state of the environment’ reports less frequently, typically every three to five years, although the most recent such report for Azerbaijan dates from 2005.

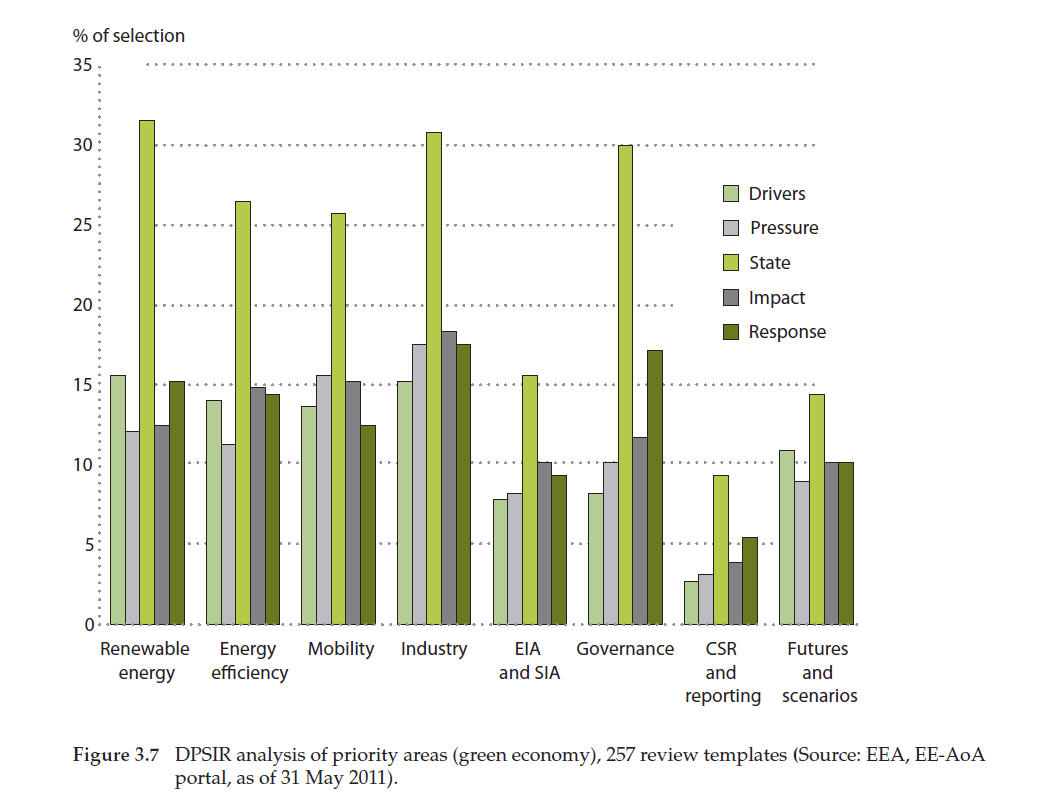

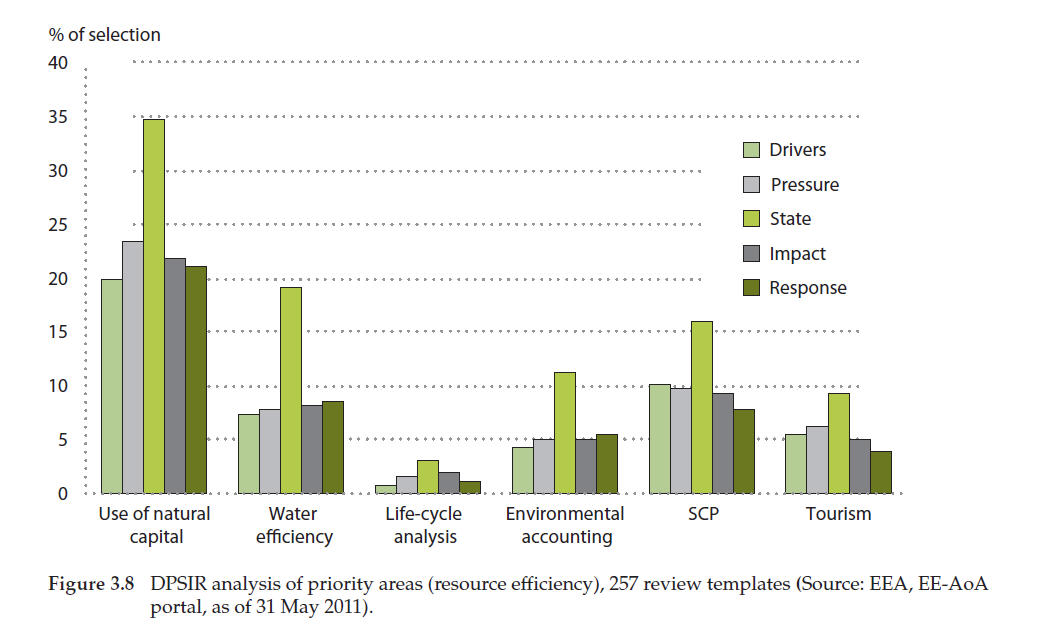

The kinds of analysis contained in assessments generally follow some variation of the DPSIR assessment framework. Figures 3.7 (green economy) and 3.8 (resource efficiency) summarise the kinds of analysis undertaken for each of the priority areas.

Figures 3.7 and 3.8 corroborate earlier observations on the coverage of priority areas and illustrate other interesting points:

- some aspects of green economy (industry, energy, governance, mobility) are more commonly discussed in assessments than others (Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Impact Assessment (SIA), Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), futures and scenarios);

- some aspects of resource efficiency (use of natural capital) are more commonly discussed in assessments than others (LCA, environmental accounting);

- as with water assessments (Chapter 2), green economy assessments are overwhelmingly focused on the state of different priorities, and this is particularly true for the more well-established or traditional areas;

- drivers, pressures, impacts and responses are analysed and discussed much less frequently.

3.2.2 National assessments and indicator sets

Despite considerable momentum in the areas of the green economy and resource efficiency over recent years, no national level assessment or indicator set focused specifically and comprehensively on the priority areas exist as yet. However, a number of countries have produced strategic assessments and plans for greening their economies. These tend to vary in their emphasis and interpretation, as illustrated by the examples in Box 3.4.

Box 3.4 shows that the emphasis of national green economy assessments varies considerably, ranging from the agriculture to the business sector, and from innovation and green jobs to energy efficiency.

In general, those countries that have been badly affected by the global recession, for example, Greece, Ireland and Iceland, place a greater emphasis on green jobs and growth as a spur to a green economy. Countries that are highly dependent on primary and extractive sectors such as Ukraine and France tend to emphasise natural resource efficiency, whilst those that have not had the benefit of extensive fossil fuel reserves including Moldova and Austria tend to focus on the energy sector.

A wide range of specific targets related to elements of the green economy are set out by countries and progress reported against indicators. These cover everything from greenhouse gas emissions and water quality to energy efficiency in new housing and spatial distribution of natural ecosystems. For example, Ukraine has a target to stabilise greenhouse gas emissions at 20 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020, whilst Moldova aims to increase forested areas from 12.1 per cent in 2010 to 13.2 per cent in 2015.

National resource-efficiency assessments in EEA member countries will be summarised in the forthcoming survey of resource efficiency policies (EEA, 2011). These provide information on resource use per person, by category for fossil fuels and biomass etc., productivity and so on.

Instead of dedicated strategic policy assessments, six broad economy-wide types of strategies or assessments commonly include references to resource efficiency: national sustainable development strategies; national environmental strategies/action plans; SCP action plans; raw materials plans and strategies; strategies and plans related to climate change; and economic reform programmes.

Box 3.4

Shades of green: differences in emphasis on green growth

Green growth in Denmark (40)

The purpose of the green growth agreement is to ensure that environmental, nature and climate protection go hand-in-hand with modern and competitive agriculture and food industries.

DKK 13.5bn will be invested in green growth until 2015 to ensure that Denmark fully meets its environmental obligations and strengthens growth and employment.

The Agreement on Green Growth incorporates:

- the Environment and Nature Plan Denmark up to 2020;

- a strategy for a green agriculture and food industry undergoing growth.

Building Ireland’s smart economy (41)

In 2009, the government’s recovery strategy sets out a framework for economic renewal, based on sustainable development principles. The strategy addresses green-collar job creation and identifies ‘enhancing the environment and securing energy supplies’ as a priority action area.

Opportunities for the environmental goods and services sector include:

- efficiency in resource and energy use;

- development of new business sectors;

- importance of indigenous (environment-dependent) sectors such as food and tourism

- environmental technologies that decrease material input, reduce energy consumption and emissions, recover valuable by-products, or minimise waste disposal problems.

State of environmental policy at the turn of the century in Russia (42)

This review analyses preconditions for green growth in Russia and the relationship between economic growth, social well-being and environmental issues. It sets out past problems that have not been solved and new urgent environmental challenges facing Russian society, which run counter to the public interest. Recommendations are focused on increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of environmental policymaking. They include changing investment priorities and greening the economy through changes to environmental and economic policies at the highest level.

Energy efficiency and transition to a green economy in Turkey (43)

A key part of Turkey’s vision for a green economy brings together all aspects of energy efficiency, from production of energy to distribution and consumption.

One of the key aims is to reduce the country’s carbon dioxide emissions. It considers pricing, competition, behaviour change and technology in all sectors of the economy. Other policy options considered are electrification of transport and changes to the building stock and to energy-using products.

However, this situation is gradually changing and a number of countries are now developing more specific strategies and assessments for resource efficiency. Examples are presented in Box 3.5.

Some transition is taking place from sector-based policies — energy efficiency, water, waste, etc. — to integrated resource-efficiency policies, in Finland, for example. Only in a few cases is the complete life-cycle considered or environmental impacts abroad taken into account. For example, Sweden has strategic objectives related to reducing the global environmental impacts of national consumption, while the Netherlands is taking the environmental impacts embedded in trade into account.

Four priority resources — energy; waste, water and minerals — are commonly assessed by countries, but beyond these, other priorities are less often assessed with consideration given to land and soil, timber/forests, biodiversity, biomass, fish, metals, and the sea and coast, depending on national conditions.

Information on strategic objectives, targets and indicators in resource-efficiency assessments shows a large variety of approaches, directions and level of detail. Strategic objectives for resource efficiency tend to be fairly general in nature, most often referring to:

- ensuring sustainable use of natural resources;

- improving energy efficiency;

- increasing recycling of waste; and

- waste prevention/decoupling waste and growth.

Other fairly common objectives include:

- sustainable management of minerals;

- improving resource efficiency;

- reducing energy use;

- increasing the share of renewable energy;

- improving water quality;

- reducing the use of water; and

- protecting biodiversity.

Several countries have set objectives and/or targets in assessments related to housing, for example energy-efficiency in buildings, appliances and electricity use (Belgium and Lithuania); mobility including increased use of biofuels in transport (Estonia, Slovakia) or fuel-efficiency standards for cars (Hungary); and food such as increasing the area of organic farming (Spain, Denmark). However, in most cases objectives and targets are aimed at efficiency improvements in technology rather than addressing consumption through managing demand, and very few countries include strategic objectives in their assessments to reduce absolute quantities of resources used.

Box 3.5

Resource efficiency assessment in the pan-European region (44)

Austria’s Resource Efficiency Action Plan (REAP) will be adopted in 2011 and is required by the National Strategy on Sustainable Development.

REAP will provide a framework and impetus for resource efficiency addressing security of supply for critical resources, specific resource groups such as renewable materials and selected economic sectors, construction.

REAP will provide a framework and impetus for resource efficiency defining several core strategies. The focus is on materials such as metals, minerals, biomass and fossil based materials. Links to energy efficiency and the efficient use of other natural resources such as water and area are covered and also addressed by the National Energy Strategy.

The upcoming REAP will be accompanied by other strategies aimed at improving resource efficiency, example e.g.: The 2010 Raw Materials Plan, the Austrian Strategy on Research, Technology and Innovation, the Energy Strategy, the existing master plans on Green Jobs and on environmental technologies, the 2010 Action Plan on Public Procurement and the upcoming Waste Prevention programme 2011.

Germany’s Ministry for the Environment leads on the National Resource Efficiency Programme, to be published in 2011. The main focus is the minimisation of impacts on the environment through raw material production and processing.

Until now, resource efficiency has been addressed in different overall strategies:

- the 2002 Federal Development Strategy, focused on the improvement of raw materials efficiency, with quantitative targets for resource and energy efficiency;

- the 2010 National Raw Material Strategy, focused on securing the availability of mineral raw materials;

- the 2008 National Energy Efficiency Plan, aimed at reducing energy consumption and improving energy efficiency;

- the 2010 High-Tech Strategy 2020, focused on innovation processes and future technologies;

- the Framework Research Programme for Sustainable Development, with several thematic focal points addressing resource efficiency;

- the 2010 National Research Strategy for Bio Economy 2030, with an overarching aim to promote the sustainable use of biological resources by bio-innovations and their application in various industrial sectors.

European Union: resource-efficient Europe — the flagship initiative under the Europe 2020 Strategy

A resource-efficient Europe is one of seven flagship initiatives as part of the Europe 2020 strategy aiming to deliver smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. This is now Europe’s main strategy for generating growth and jobs, backed by the European Parliament and the European Council. Member States and the EU institutions are working together to coordinate action to deliver the necessary structural reforms. This flagship initiative aims to create a framework for policies to support the shift towards a resource-efficient, low-carbon economy which will help to:

- boost economic performance while reducing resource use;

- identify and create new opportunities for economic growth and greater innovation, and boost the EU’s competitiveness;

- ensure security of supply of essential resources;

- fight climate change and limit the environmental impacts of resource use.

Source: EC, 2011, p.3: http://ec.europa.eu/resource-efficient-europe/pdf/resource_efficient_europe_en.pdf.

3.2.3 Thematic assessments

Many countries complement wide-ranging ‘ state of the environment’ reports with more focused, thematic assessments — both stand-alone reports or as chapters in broader reports — relating to sectors such as energy or topics such as green jobs. Indeed, while the concept of green economy may not be explicitly part of national policies, the underlying ideas of a green economy are an implicit component. The most obvious examples of this are renewable-energy and energy-efficiency measures, which are promoted by all countries to some extent and are part of all definitions of a green economy. For example, UNECE (2010) is a wide-ranging regional assessment, providing an overview of the energy sector and policy framework for Belarus, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova, whilst UNDP (2007) considers the prospects for renewable energy in Uzbekistan, and UNFCCC (2010) relates many aspects of the green economy to climate change in Armenia. Other examples are provided in Annex 3.1.

Examples of specific thematic reports are presented in Box 3.6.

Key trends in thematic assessments include:

- well over half relate to energy and most of these are focused on the status of, and potential for, renewable energy. This is the case in all parts of the pan-European region;

- assessments related to energy also contain significantly more statistical detail (for example, breakdowns of energy by type — heat, transport, electricity, etc.) and technologies (including wind, wave and biomass) than is available for other sectors and priority areas;

- thematic assessments range from strategic documents to inform political priorities to influencing documents from sector and trade associations, and from economy-wide to focused, sector-based reports;

- thematic assessments are produced nationally, regionally and internationally by a wide variety of public institutions (for example, European Commission 2011 progress report on renewable energy (45) and the private sector (for example, the European Renewable Energy Council (46), which reports renewable energy generation and other statistics for EU-27 Member States);

- regional or global bodies tend to link assessments to political priorities (for example, preparations for the Rio 2012 conference) or to changes in awareness (for example, increased interest in water footprint); national and private bodies tend to focus more on specific topics or sectors;

- some thematic assessments relate to more general themes or to sectors outside the standard definitions of green economy. These include agriculture, tourism, manufacturing, construction, mining and health.

Box 3.6

Examples of thematic reports across the pan-European region

Renewable energy in Croatia. (47) The EBRD is assisting with Croatia’s Renewable Energy Development Initiative, a regular assessment (latest version 2009) of the state of and potential for all types of renewable energy, including wind, biomass, solar, geothermal and hydroelectric. This follows the opening up of Croatia’s electricity markets in 2007. A number of incentives, including feed-in tariffs, are in place.

Energy efficiency in Luxembourg. (48) The National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency describes the current state of the energy sector and focuses on current and future measures to improve energy efficiency (and renewable energy generation) in the economy as a whole and sector by sector.

Waste management in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. (49) The 2008–2020 Waste Management Strategy considers the generation, treatment and use of all types of non-hazardous and hazardous waste, including from mining and emissions from incineration plants. Policy options considered include waste as a source of renewable energy, obligations and responsibilities for manufacturing, business and domestic sectors, education and research.

Transport in Slovakia (50) A 2009 assessment of transport and its impact on the environment in the Slovak Republic uses the DPSIR approach and reports a suite of indicators to describe various issues relating to transport, including policy measures, emissions and renewable fuels.

3.2.4 Assessments with country profiles

A variety of organisations produce a range of green economy related reports and assessments that contain information on specific countries. These are generally based on secondary, evidence-based information from international or national institutions and cover a number of topics of relevance to green economy (for example, CIA World Factbook) (51).

Country profiles vary in type and coverage. Some countries are more comprehensively covered by green economy related assessments than others. This is partly because of the number of assessments undertaken by regional bodies to which these countries belong (as in EEA, 2010). But it also reflects socio-political priorities, with countries from Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia for example attracting greater attention from organisations with an interest in development or reconstruction and investment.

The basis of, and approach to, assessment also varies, bringing in organisational thought, strategic visions, detailed action plans and data-reliant assessments (e.g. benchmarking studies).

Global organisations leading on country profiles include the UN system, the World Bank and the World Resources Institute, a global environmental think tank. However, even across UN organisations, green economy concepts have not yet had a full impact on regular country assessments. For example, the FAO produces regular assessments of agricultural production, with accompanying data and indices, but these are not discussed in terms of resource efficiency or contributions to broader objectives.

Some country assessments by global organisations are driven by the strategic priorities of the organisation and are designed to feed into or influence significant global events. For example, the UN has prepared country assessments to feed into summits held as part of various conventions. These typically include assessments of natural-resource management (for example, water, forests and agriculture), energy use, social justice and poverty eradication.

Others are aimed at increasing awareness and knowledge. Examples include the Environmental Performance Index (52) and the World Resources Institute’ s Earthtrends series (53). The latter includes a comprehensive set of maps and a searchable database covering all countries, including the pan-European region. Information comes from a range of sources and is updated on an ad-hoc basis as new priorities are identified or as new information becomes available.

Other country level assessments by international organisations are focused on specific themes or topics. For example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) maintains a database of regularly updated energy statistics, covering electricity, heat, oil, renewable and so on.

At a regional level, environmental performance reviews (EPRs) are undertaken by OECD and UNECE (54). These reviews are particularly relevant to green economy and resource efficiency and have three main objectives:

- helping countries in transition to improve their management of the environment by establishing baseline conditions and recommending better policy implementation and performance;

- promoting continuous dialogue between UNECE member countries by sharing information about policies and experiences;

- stimulating greater involvement of the public in environmental discussions and decision-making.

The third cycle of UNECE environmental performance reviews from 2011 is currently being prepared and it is proposed to include aspects of green economy, specifically including a section on ‘ Environmental governance and financing in a green economy context’ (55).

The OECD review programme has similar green economy related aims but it also includes targeted recommendations designed to reinforce national environmental policy initiatives. The third cycle of OECD performance reviews, launched in 2009, will sharpen the focus on performance and on selected issues that are of high priority in the reviewed countries.

The EEA, with support from its European Topic Centres, also produces a number of comparable datasets with information on SCP, resource and waste management in Europe. These are aimed at both decision-makers and the public (see for example ETC/SCP, 2011).

Organisations with a smaller geographical focus also produce country assessments covering specific areas. For example, the Nordic Council assesses annual trends in land use and natural resources, emissions, global warming and energy use.

Finally, in the EEA’ s most recent five-year ‘state and outlook’ report (see Box 3.7), the country assessments include several areas which are related to the green economy and resource efficiency, including renewable energy, energy productivity, material productivity and recycling quotas for different waste streams.

Box 3.7

The European environment — state and outlook 2010

SOER 2010 provides a set of assessments of the current state of Europe’s environment, its likely future state, what is being done and what could be done to improve it, and how global developments might affect future trends.

The European environment — state and outlook 2010 is aimed primarily at policymakers, in Europe and beyond, involved with framing and implementing policies that could support environmental improvements in Europe. The information also helps European citizens to better understand, care for and improve Europe’s environment.

The SOER 2010 ‘package’ includes four sets of assessments:

- thirteen Europe-wide thematic assessments of key environmental themes;

- an exploratory assessment of global megatrends relevant for the European environment;

- country assessments of the environment in individual EEA member and cooperating countries;

- a synthesis — an integrated assessment based on the above assessments and other EEA activities.

Source: http://www.eea.europa.eu/soer.

3.3 Highlights of green economy related assessments

This section considers how assessments might develop and be used in future, including the types of analysis that could be included, key concerns and emerging issues; and the main gaps in current assessments.

3.3.1 Types of analysis

A number of main threads can be identified from the analysis presented in this chapter so far that should help to guide future assessments on the green economy.

As has been seen, green economy is defined in many ways. Depending on the organisation(s) involved, the region and the context, it can refer to sectors (for example, land, water), topics (for example, SCP, pollution), principles (for example, fairness, polluter pays) or policies (for example, economic instruments, environmental impact assessment). It can also be used to describe an underpinning strategy, such as the mainstreaming of environmental policies or a supportive economic structure. This is why national assessments generally talk about green growth or greening the economy — indicating a dynamic rather than static process.

Only global assessments currently tackle such definitional issues. This assessment of assessments did not identify any national assessments that integrate all the specified elements of the green economy. This perhaps reflects the lack of an agreed definition and the fact that it is still an emerging concept. National assessments generally cover traditional elements of green economy but, driven by global policies and frameworks, new areas are emerging that need to be considered.

Given the nature of the subject, green economy and resource efficiency offer ideal opportunities for integrated assessments that assess key issues across sectors and themes. This is starting to emerge as with LCA in the Netherlands and Sweden. In Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, recent assessments supported by the World Bank aim to raise awareness among policymakers of the need to accelerate and enhance implementation of environmentally sustainable practices across the agricultural and forestry sectors (56).

Integrated assessments also require clear institutional structures and mandates. A number of organisations are currently involved in assessments and in future these will need to work together and coordinate more effectively. This includes private organisations, which have much to offer in terms of data, knowledge and influence on decision-making. One example of this is the recently formed Global Green Growth Institute (see Box 3.8).

The expansion of areas to which green economy concepts have been applied has also contributed to an increasing size and detail of assessments. This in turn leads to a general impression that there is too much information to be assimilated.

Whilst future assessments should be more focused, they should also take account not just of the environmental state of the main priority areas, but also the drivers, pressures, impacts and responses. Related to this, assessments need to clearly address or link to policy questions and objectives if they are to be most useful to decision-making.

Box 3.8

Global Green Growth Institute

Founded in June 2010 and based in Korea, the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) is a globally represented, non-profit institute dedicated to the promotion of economic growth and development while reducing carbon emissions, increasing sustainability, and strengthening climate resilience. GGGI is founded on the belief that economic growth and environmental sustainability are not merely compatible objectives, but are mutually necessary for the future of humankind.

GGGI currently supports several projects in partner countries through programme development, implementation, capacity building, best practice sharing, and the provision of grants to local institutions. Through its work, GGGI seeks to position the green growth model as one that is both practical and effective in the pursuit of economic growth and sustainable development.

From 2012, GGGI will be fully converted into an international organisation operational on a global scale. Its aim is to establish itself as the institute of choice for tools, methodology, and data related to green growth. It will have a live database of policies and institutions and their performance in different countries, enabling the Institute to be on the leading edge on advising on implementation of plans.

In May 2011, the GGGI opened its first regional office in Copenhagen.

Indeed, currently, there is often no clear link between an assessment and the relevant decision-making body or bodies, and many assessments do not clearly articulate the objectives and scope or the key questions to be answered. The impression given by many assessments suggests that they follow rather than inform policymakers or where they do try to inform policy they are ignored or only partly addressed in the policymaking process. This may be because many assessments are produced only once, or very occasionally, so there is no regular cycle linking monitoring and assessment to measures previously proposed or adopted in order to evaluate progress and the need for further action.

Success here requires a green economy strategy to be at the very heart of the national or regional decision-making process. Currently, assessments address policy questions in specific but generally narrow areas, for example, related to increased proportion of renewable energy, to green public procurement or to green jobs. It is less clear how assessments, even those of the more strategic variety, are being used to drive economic policy in general. If the green economy is about transforming the way a nation produces and consumes, trades and is governed, then assessments should be at the very heart of economic and political strategies, rather than at the fringes.

A clear framework is also required to guide assessments, including targets, ways of measuring progress and evaluating policy effectiveness. This should include adoption of green national accounting alongside current measures such as GDP. Green accounting seeks to factor the use of natural resources into mainstream national accounting. This requires an understanding of the value of such resources, including the benefits they deliver and the impacts of any depreciation or loss. Green accounting provides a fuller picture of a nation’ s economy for decision-makers. To date, it has not been widely adopted, although there are moves in a number of countries to improve understanding and to run natural resource accounting alongside conventional national accounts.

An example is the Development of natural resources value accounting in the Russian Federation, commissioned by the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment and the Federal State Statistical Service. The aim of this assessment is to study possibilities for harmonising national and international approaches to valuing natural capital, and providing government authorities with complete, accurate and scientifically substantiated data on the current state of environmental and economic valuation of natural capital in the Russian Federation. The assessment identified a number of priority needs and actions in order to improve the system of valuation of natural resources in the Russian Federation. These include establishing an integrated and regularly updated information system of environmental and economic valuation of natural capital, strengthening and improving inter-agency coordination, cooperation and training for Federal State Statistical Service specialists on natural resources accounting.

Finally, assessments should be publicly available and include web-based portals and databases, where relevant information and data can be provided in a common format, shared and quickly accessed.

3.3.2 Key concerns and emerging needs

In all regions, a large proportion of the assessments in the EE-AoA review template identified concerns (82 per cent) and emerging needs (77 per cent). These generally relate to the specific nature of the assessment, but some general observations can be drawn.

One key concern is that the assortment of topics and sectors related to green economy concepts enables organisations to select the aspects that are most relevant to or suitable for them. This flexibility is a double-edged sword. Whilst it helps to bring issues of environmental protection to a broader audience, it may ‘ water down’ the green economy concept to the point that it becomes ineffective or meaningless.

This is similar to the problem that has afflicted sustainable development, which has been widely adopted and, as a result, used to describe and justify a plethora of policies, plans and strategies. There is an additional risk for the green economy in that the new discourse could be used to justify unilateral trade protection measures, as nations introduce domestic production quotas or targets, and offer subsidies or other economic incentives to ‘ home grown’ industries and jobs. This could strengthen inequalities between rich and poor nations and hinder their development (UNCSD, 2011).

There is therefore a need to clearly define and agree what we mean by a green economy, and to adopt measures that take account of international, as well as domestic, impacts on natural resources and welfare.

A major concern identified in most assessments is the institutional complexity involved in the responsibility for, and production of, green economy assessments. Issues cited typically include poor coordination, weak environmental legislation/regulation, unenforceable multilateral agreements where transboundary issues are involved and the inability of environmental ministries and institutions to bring about effective change at the national level. An example is implementation of the polluter pays principle, which is an aspiration in many countries (including all EU Member States), but difficult to implement because of, for example, difficulties in identifying the polluter.

Lack of effective change can also come about through insufficient funding or technical expertise, a lack of available economic instruments, corruption (which can reduce the attractiveness for investors in green economy) or political emphasis on other issues. It remains the case that green growth and resource efficiency initiatives are often perceived as costly and irrelevant in the current economic climate. Indeed, a number of assessments in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia state that environmental protection is simply not a government priority.

This institutional complexity and inertia also make it harder for green economy assessments to get purchase at a national level, as they are overtaken by narrower short-term priorities. There is clearly a need to establish mechanisms for a central coordination of work to ensure the transition to a green economy, as is starting to emerge in some countries including Sweden and Germany. Other countries, such as Finland, have set up specialised agencies to support policy development.

The increasing tendency and need to involve institutions with different perspectives often leads to overlapping competencies, unclear responsibilities and tensions or conflicts between different groups and difficult trade-offs. For example, better understanding of LCA may lead to calls for less dependence on imported food, but this generally increases demand for water and pesticides domestically, with subsequent local impacts on pollution and resource use.

Here, countries need encouragement to integrate assessments and to be provided with a more clearly defined framework and methods for such assessments (e.g. ecosystem services approach, integrated natural resource accounting).